The title of the conference was ‘Speaking Truth to Power: Making Special Collections Work in Times of Recession’, so fundraising, advocacy and outreach were major topics of conversation. I’ve written up a narrative account of the conference for the East of England branch newsletter, Sunrise, which should be available later in the Autumn. What follows here are my thoughts arranged under what I felt were the main themes to emerge from the conference. I’ve compiled a separate list of useful webpages, projects, reports and articles.

It’s fair to point out that I’ve always traditionally been sceptical about what university development offices do: I’ve had my fair share of half-hearted begging letters from my old college, and feel pretty cynical about their attempts to wring money from me (they know I’m a librarian, so I really don’t know why they try...). Remarkable to relate, this conference really changed the way I feel how we can engage with fundraising, and so my reflections seemed to have turned out more like a manifesto.

Show Don’t Tell

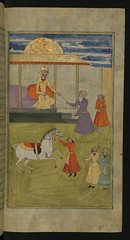

Our collections are our best and most powerful advocates, not only for themselves and for the library, but for the whole institution. The collections are most effective when people see and touch them up close and personal. The ‘thingyness’ of our things matters; a digital reproduction is nice, but it just isn’t the same as the real thing, and allowing people not only to see, but to touch, gives them a big thrill and makes them feel important and valued. Christopher Parking described that the physicality of objects is an important part of contemporary museum education practice, where the focus is on handling collections, kinasthetic learning, and enquiry-based learning. School groups no longer just follow clipboard trails around objects safely kept behind glass.We should be getting the important people inside and outside our institutions into our libraries to see just what it is that makes us special. It’s no use just writing an email or a report describing what we hold: people have to come and see it to really understand. Obviously it’s not always feasible to let everyone handle our objects, but don’t discount the impact it can make when it is possible to allow that.

Know Your Collections

We, as librarians, are fundamental in making our collections work, as we’re the people who know most about them. We should be prepared to market ourselves as the people who can interpret the collections. There's something in most special collections that will appeal to everyone and anyone, so librarians are vital because we know what that item will be. This can make a big difference when, for example, the development office are bringing round potential donors. We’re also important because we’re the people who know best just what a difference extra funding could make.Our knowledge as librarians is what can make a big difference to academics, too. They need access to our holdings to support their teaching, and they need access to our knowledge to help further and inform their research. Central to getting our collections used in research is getting them all catalogued, not only locally but as part of national and international indexes, and making the catalogue data available in useful ways.

It’s no longer acceptable for institutions to have basements of unknown collections, often the legacy of indiscriminate and undocumented collecting in the past. So we need to take the initiative in working out what we have. This is something that Manchester Public Library have been doing during the current refurbishment: they’ve been assessing what was, and what should be, stored in their closed stacks, and working out how that can be used in the future.

Know Your Institution

It’s not always easy to do, but you need to work out who has the power in your institution, and be prepared for the fact that once you’ve identified who that is, they’ll probably keep changing. Alison Cullingford noted that people can have positive power (they can make things happen) and negative power (they can stop things happening).Mark Nicholls gave a very clear account of the ways in which we can gain power for ourselves and influence those others who hold the positive and negative power. He notes that "The worst mistake of a college (or any) politician is to be absent": we should do what we can to get on as many committees as possible and to cultivate allies on the others. It’s important, he noted, to realise that those in charge can and will make decisions quickly when the time is right. We have to be good at working out what ideas are right for the moment. This gets easier as time goes on: one successful project, and attendant praise for the institution, will prime the organisation (and its nay-sayers) for further success.

Neil MacInnes and Judy Faraday both described the ways in which they were using special collections to further the aims and agendas of their institutions. Manchester Public Libraries special collections are being used to engage communities that the local authority holds as priorities, including black and ethnic minority communities, place-based communities, and young people. The materials held by the John Lewis archives and the community archives centred around the locations of John Lewis stores helps to support the partnership’s business cycle. It does this both by providing materials for business use, including publicity and design, but also by creating community support and interest. I suppose that you could call this latter effect ‘soft advertising’ - in any case, it’s part of the partnership’s commitment to corporate responsibility. It’s important to be explicit about how your activities are supporting the mission and goals of your organisation. Don’t just do it, but make sure everyone knows you’re doing it.

Know Your Audience(s)

We have lots of different audiences for our collections, activities and fundraising efforts. Our traditional audience, academic readers, are still very important. Anne Welsh commented that their voices can be important in times of uncertainty, and that their support for services and collections can be vital.There’s a general support for libraries and special collections amongst the general public. Although there’s often a rather clichéd and unfair impression that we’re just old and dusty, this support is still something we can and should work with. Richard Ovenden mentioned the one-day display of a copy of Magna Carta at the Bodleian: lots people will queue up to see something if you advertise it well, and this will generate positive publicity for your institution.

When considering external funders, Mark Nicholls advises that we can improve our image easily for example by producing a professional and attractive annual report. Oliver Urquhart Ivine described British Library work creating partnerships such as that with the Qatar Foundation. They took time and effort to research potential donors in depth, and to plan how they will approach and encourage potential donors. This advice chimed with Mark Nicholls caution that we have to anticipate potential objections to our plans and be prepared to knock them away one by one.

When planning fundraising efforts, Sean Rainey commented that it’s important to realise that there’s a difference between funding priorities and fundraising priorities. We have to recognise what things donors will and won’t be prepared to donate towards. We won’t have much success campaigning for retrospective conversion, small facilities improvements, and supplies and equipment purchases, so we need to look critically and objectively at our plans and decide what we can realistically achieve via which means.

Don't Be Complacent

In straightened times it’s important to keep ourselves front and centre in the minds of the people who make the decisions. This might seem mercenary and drastic, but it can make all the difference. There are plenty of collections and collecting areas that are sadly under risk. As well as recent high-profile threatened libraries, Richard Ovenden and Alison Cullingford both identified twentieth-century collections that haven’t traditionally been regarded as ‘special collections’ as areas that may not be receiving the attention they need now to be preserved for the future.Fundraising, I think, isn’t something that comes naturally or easily to librarians. We like to think that the importance of our collections is not merely monetary, and that their cultural and intellectual value will ensure they receive adequate support without our having to bring out a begging bowl. But that, sadly, isn’t the case. We need to make the case for our collections, and to use the existing mechanisms for fundraising (development offices, funding bodies, donors, and so on) to attract support. Sean Rainey ended his paper by enjoining us not to let fundraising slip down the to-do list, and I’ll echo what he said: start working on it now.

0 comments:

Post a Comment